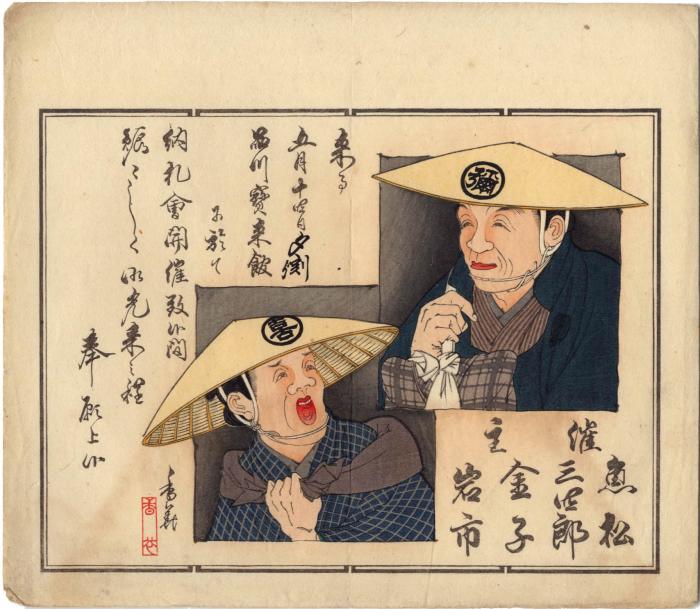

Kanō Tomonobu (狩野友信) (artist 1843 – 1912)

Portraits of Yajirobei (彌次郎兵衛) on the right and Kitahachi (喜多八) on the left

ca 1912

8.5 in x 7.375 in (Overall dimensions) Japanese woodblock print

National Museum of Asian Art - a similar print from the same period Portraits of Kichibei and Yajirobē

Illustration from the Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige (東海道中膝栗毛), abbreviated as Hizakurige and known in translation as Shank's Mare is a picaresque comic novel (kokkeibon) written by Jippensha Ikku (十返舎一九, 1765–1831), about the misadventures of two travelers on the Tōkaidō, the main road between Kyoto and Edo during the Edo Period. The book was published in twelve parts between 1802 and 1822.

"The two main characters, traveling from Edo to Kyoto on their pilgrimage to the Ise Shrine, are called Yajirobē (彌次郎兵衛) and Kitahachi (喜多八). The book, while written in a comical style, was written as a traveler's guide to the Tōkaidō Road. It details famous landmarks at each of the 53 post towns along the road, where the characters, often called Yaji and Kita, frequently find themselves in hilarious situations. They travel from station to station, predominantly interested in food, sake, and women. As Edo men, they view the world through an Edo lens, deeming themselves more cultured and savvy in comparison to the countrymen they meet."

"Hizakurige is comic novel that also provides information and anecdotes regarding various regions along the Tōkaidō. Tourism was booming during the Edo Period, when this was written. This work is one of many guidebooks that proliferated, to whet the public's appetite for sight-seeing."

"Some of the episodes from this novel have been illustrated by famous ukiyo-e artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige, in his One Hundred Views of Edo."

This information is taken directly from a Wikipedia site.

****

Who was Jippensha Ikku?

W.G. Ashton in his brief summary of the work of Jippensha Ikku said on pages 369-370 in A History of Japanese Literature, published by William Heinemann in 1907: "Jippensha Ikku (-?-1831) was the son of a petty official of Suruga. His early life was very unsettled. We hear of his holding small appointments in Yedo and Ōsaka, and his name appears with those of two others on the title-page of a play written for an Ōsaka theatre. He was three times married. On the first two occasions he was received into families as irimuko that is, son-in-law and heir. In Japan such situations are notoriously precarious and unsatisfactory. "Don't become an irimuko” says the proverb, “ if you possess one go of rice.” Ikku did not remain long with either of these wives. Very likely his parents-in-law objected to his Bohemian habits and dismissed him. In his third marriage he was careful not to sacrifice his freedom. Ikku's biographers relate many stories of his eccentricities. Once when on a visit to a wealthy citizen of Yedo he took a great fancy to a bathtub. His host presented it to him, and Ikku thereupon insisted on carrying it home through the streets, inverted over his head, confounding with his ready wit the passengers who objected to his blindly driving against them."

"One New Year's Day a publisher came to pay him the usual visit of ceremony. Ikku received him with great courtesy, and prevailed on him, somewhat to his bewilderment, to have a bath. No sooner had his guest retired for this purpose than Ikku walked off to make his own calls in the too confiding publisher's ceremonial costume, Ikku not being possessed of one of his own. On his return, some hours later, he was profuse in his thanks, but said not a word of apology."

"When he was engaged in composition he squatted on the floor in a room where books, pens, inkstone, dinner-tray, pillow, and bedding Jay about in confusion, not an inch of free space being left. Into this disorderly sanctum no servant was ever admitted."

"Ikku's ready money went too often to pay for drink, and his house lacked even the scanty furniture which is considered necessary in Japan. He therefore hung his walls with pictures of the missing articles. On festival days he satisfied the requirements of custom, and propitiated the gods by offerings of the same unsubstantial kind."

"On his deathbed he left instructions that his body should not be washed, but cremated just as it was, and enjoined on his pupils to place along with it certain closed packets which he entrusted to them. The funeral prayers having been read, the torch was applied, when presently, to the astonishment of his sorrowing friends and pupils, a series of explosions took place, and a display of shooting stars issued from the corpse. The precious packets contained fireworks."

On page 371 Ashton notes: "The Hizakurige was published in twelve parts, the first of which appeared in 1802, the last not until 1822. It occupies a somewhat similar position in Japan to that of the Pickwick Papers in this country, and is beyond question the most humorous and entertaining book in the Japanese language."